Rupert Murdoch had already been living in New York for three years before most of the city’s journalism establishment cared much about who he was. Sure, he owned a few papers around the country, and he was known for having turned The News of the World from a winkingly naughty paper that hid behind a screen of Victorian propriety into the screaming scandal sheet that it remained until this year. And of course he was also known for being an Australian press lord. He was that even in 1976, when Elisabeth, Lachlan and James were 8, 5 and 4. But in New York, he was quiet, a one man sleeper cell getting the feel for a new place—making friends with Clay Felker, the man who bought New York magazine from the ashes of the New York Herald-Tribune and turned it into the first city magazine, and then, through Felker, Murdoch made the acquaintance of Dorothy Schiff, the longtime Roosevelt liberal (and rumored Roosevelt paramour) who had turned America’s oldest newspaper into a tabloid aimed at a diminishing, mostly Jewish, educated middle class readership.

Rupert Murdoch had already been living in New York for three years before most of the city’s journalism establishment cared much about who he was. Sure, he owned a few papers around the country, and he was known for having turned The News of the World from a winkingly naughty paper that hid behind a screen of Victorian propriety into the screaming scandal sheet that it remained until this year. And of course he was also known for being an Australian press lord. He was that even in 1976, when Elisabeth, Lachlan and James were 8, 5 and 4. But in New York, he was quiet, a one man sleeper cell getting the feel for a new place—making friends with Clay Felker, the man who bought New York magazine from the ashes of the New York Herald-Tribune and turned it into the first city magazine, and then, through Felker, Murdoch made the acquaintance of Dorothy Schiff, the longtime Roosevelt liberal (and rumored Roosevelt paramour) who had turned America’s oldest newspaper into a tabloid aimed at a diminishing, mostly Jewish, educated middle class readership.

And then Rupert struck, buying the Post from his New York social scene acquaintance, Dolly Schiff. She was a cantankerous, capricious publisher, to be sure, and even those writers who respected her and were loyal to her didn’t seem to like her much. But still, the sale of the Post to the Australian press lord? That was a story (one, it seems, that the Post itself was scooped on).

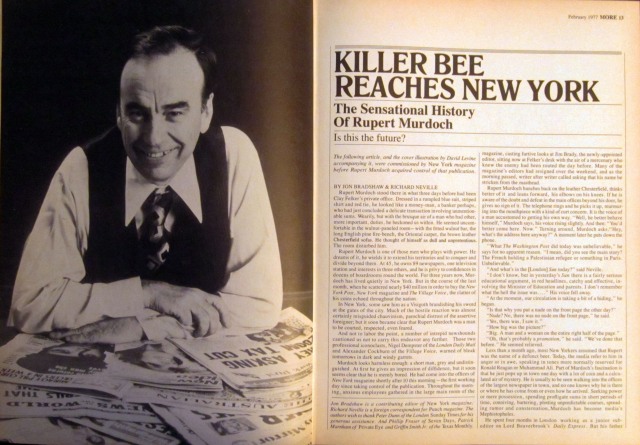

Clay Felker wasn’t going to let this story get away, though. He too was unpredictable as an editor, but most of the time, people threw in words like “extremely talented” or even “genius.” The man had more or less invented a category of media, and had nurtured the careers of “New Journalists” like Tom Wolfe, Jimmy Breslin and his own wife, Gail Sheehy. So Felker jumped into editorial action when the Post/Murdoch news broke. New York commissioned cover art from illustrator David Levine, known for his New York Review of Books caricatures. Levine came back with a portrait of Rupert as a killer bee, his stinger pointed toward the base of the new World Trade Center towers, and his ham-pink, crosshatched face recognizable at age 45 even to someone who was born a month or two after the picture was commissioned, and who therefore somehow assumes that Murdoch started life as a septuagenarian.

And for the profile itself, Felker’s magazine enlisted a pair of writers, showing in his choices some of that editorial acumen he was known for. Presumably to handle the New York angle, but with knowledge of Britain, Felker charged Jon Bradshaw, a New York contributing editor who had also written a book about backgammon, of all things, and had worked as a writer in England (at the Sunday Times, long before Murdoch bought that, too). And to get the Australian side of things, Felker turned to Richard Neville, the co-founder of an Australian satirical magazine called Oz, a magazine that between its Australian and English versions, got Neville involved in no fewer than three obscenity trials (and earned him the honor of being played in movies by both Hugh Grant and Cillian Murphy).

And then, before they went to press, the story and the illustration were killed. Rupert Murdoch had bought New York.

A January, 1977 article in Time claims that “Felker thought better of it,” though it also implies that the illustration was a reaction to the news that Murdoch had wrested New York away from Felker, which seems bizarre, unless it was commissioned in the period when Murdoch was still wresting and Felker was still clinging to his beloved creation. What seems more likely is that the story and cover illustration were commissioned in that brief period (less than two months, Thanksgiving to New Year’s!) between Murdoch’s purchase of the Post and his takeover of New York. And if Rupert Murdoch owned New York, there was no way down under that it would be running a comprehensive cover story about the boss’s past.

The story did eventually run, just not in New York. Across town, a small but influential journalism review called More had been publishing the work of an impressive slate of journalists and critics since 1971 (though the subscription list would be sold to the Columbia Journalism Review the next year). According to the italicized blurb that introduced the article in the February, 1977 issue of More, the article and illustration (which More ran on its own cover) “were commissioned before Rupert Murdoch acquired control of that publication.”

More had already run a pretty extensive package on Murdoch’s Post coup, just the month before. The January number featured an article on how Murdoch’s takeover of the Post might result in “old-fashioned newspaper war,” especially if the Daily News dared to enter the evening newspaper market (though of course it was the Post that switched to mornings). There was a collection of memoirs of Dolly Schiff by former Post people Pete Hamill, and Nora Ephron and by indy muckraker and proto-blogger I.F. Stone. (Frank Rich’s recent piece, published in New York as serendipity would have it, would have fit in just fine in this collection.) Doug Ireland, a veteran of the Post, as well as New York and a third publication that wound up under Murdoch in the New York deal, the Village Voice, wrote the main news story, as well as a sidebar on how the Newspaper Guild would handle Murdoch if he tried to fire their unionized employees. “He ain’t gettin’ rid of nobody in Guild jurisdiction,” Ireland quoted the executive vice president of the Guild as saying. “We don’t exist as a severance paying mechanism.” As Rich points out in his piece, Murdoch didn’t have to fire them. He just drove them (most of them, anyway) away.

But even with all of this prior coverage, how could More turn down the opportunity to run the profile of Rupert Murdoch that might have been inspired by Rupert Murdoch’s looming takeover of the magazine that commissioned it, and that was doomed by the fact that Rupert Murdoch conquered that magazine, leaving story and illustration unceremoniously—or even better, ceremoniously—impaled on a spike?

Given what we now know about Rupert Murdoch, the profile isn’t shocking (though it is slightly odd that Neville quotes himself in the third person). We learn about his charlesfosterkanian beginnings in Australia, redeeming his father’s lost newspaper career. We learn about his first attempt to own a “respectable” paper when he founds The Australian. We learn about the takeover of The News of the World. There’s even a seven-column spread of 21 covers of the Daily Mirror from 1976, most of which have pretty prosaic headlines, given the “Headless Body in Topless Bar” excesses that were to come at the Post.

The one story that sticks out, and except for this piece in The Daily Beast, seems to have largely been forgotten is the shocking and incredibly relevant (given the centrality of Milly Dowler to Rupert’s current kerfuffle) story of Digby Bamford. Here is Bradshaw and Neville (and given the kicker to this story, likely more Neville than Bradshaw)’s version of the story in full:

One day in March 1964, a bewildered migrant walked into the offices of Murdoch’s Daily Mirror, clutching his daughter’s diary in his hand. Appalled by what he had read, he sought advice from the seemingly omnipotent arbiters of community taste. For other reasons, the Mirror shared the migrant’s concerns and decided to print the contents of the little red book on its front page: “Sex Outrage in School Lunchbreak,” the Mirror blared. Reproduced passages of the girl’s diary spoke of secret rendezvous and sexual encounters with schoolmates. As a result of the publicity, the 14-year-old girl and her “boyfriend,” Digby Bamford, were expelled from school. And for Murdoch’s readers, that is where the story ended. It was never reported that the following day, young Digby Bamford was found hanging from a clothesline in his backyard; nor was it ever reported that a pathologist from the children’s welfare department filed a report of the incident in which he stated that the 14-year-old girl was still a virgin.

Only Richard Neville’s “obscene” publication, Oz, printed the whole story at the time.

It’s a shame that More isn’t digitized, though the magazine’s founding editor, Richard Pollak, tried and failed to get Google to add its press run to its digital archive. The Bradshaw and Neville profile would have made a more than worthy addition to longform.org’s recent compilation of Murdoch profiles. But what this 1977 profile in More—one which was published almost exactly my entire lifetime ago—shows, is that we knew who Rupert Murdoch was long before the NOTW phone hacking scandals. And even then it was old news, as Bradshaw and Neville saw:

Since 1952 he has built his bordello of newspapers across three continents. For 25 years, his papers have been purveyors of cheap thrills, inciters of death and false alarms, advocates of obsolete prejudices, saboteurs of taste, hawkers of back seats and second fiddles, of cocks and bulls.

So our assessment today of Murdoch isn’t hindsight. It’s just sight. We’ve seen it all along. It’s just that until now, we’ve also played along. The subhead to the More story asks, “Is this the future?” And the answer, of course, is yes. Yes it was.

About time this story was retold – thanks so much.

Is there any way of getting hold of that 1977 issue of Moore?

All the best, Richard Neville

Mr. Neville:

Send me an email at kevinmlerner@gmail.com. I can try to put you in touch with the owners of the extant copies of which I’m aware, and I would love to interview you about More at some point if you are willing.

Best,

Kevin Lerner

Depending on the sins you’d like to see Murdoch and Co. suffer for, it would seem that if one wants him and News Corp. to fail, one wants the enrite current industry to fail, as well. Propping up not just old, but truly obsolete, business models should never be rewarded regardless of the perceived quality of their content. Because the business model can no longer help but taint that content directly or indirectly. Whether it be for fear of backlash from advertisers, or concern over possible litigation, or simply the inability to respond with the swiftness the 21t century now requires of information outlets, journalism needs to change, and change drastically. It will. Regardless of whether or not Disney, News Corp., or the rest of the conglomerates follow, it may very well be unavoidable. The only thing that has even a chance at stopping it, is the issue of net neutrality and its stepchild of metered bandwidth consumption for consumers and content providers.

I’ve come across it on the internet, and relooked it up a few years ago, it was still there. As a matter of fact I’m looking for it now. Tom Watson, (the English M.P.) seems to be doing a good job in bringing Murdoch’s sins to light, it would be a good idea to post a link to him. I’ve attempted to spread the article around, myself. I think many people underestimate the horrors that this man can achieve! – even now.